When I write women, I don’t create them as symbols or archetypes. They are people, shaped by the worlds they inhabit. Some fight against their circumstances, some carry wounds that refuse to heal, and some embrace the darkness that has been thrust upon them. A reader who read Dakhma once told me that Anahita gave her hope. She said that she would love to read more such strong female characters in Indian fiction, especially in commercial fiction. Irony is that the women in my books are not part of Life is What you Make it or Too Good to be True world, but rather in a universe of horror and thriller fiction. Nevertheless, one thing remains constant—they are never passive. They resist, they suffer, they act.

On Women’s Day, I find myself reflecting on the women I have written—how they have shaped my stories and, in turn, how they have been shaped by the world around them. From Bhram to Dakini to Dakhma, these characters embody different shades of survival and defiance, but their struggles also highlight an unfortunate truth: strong women are difficult to be accepted, especially in film and literature (commercial fiction). The industry still hesitates to embrace narratives where women are not just emotionally complex but also central forces of action and consequence.

Mamta Mathews vs. Karmi Rani: Two Worlds, Same Chains

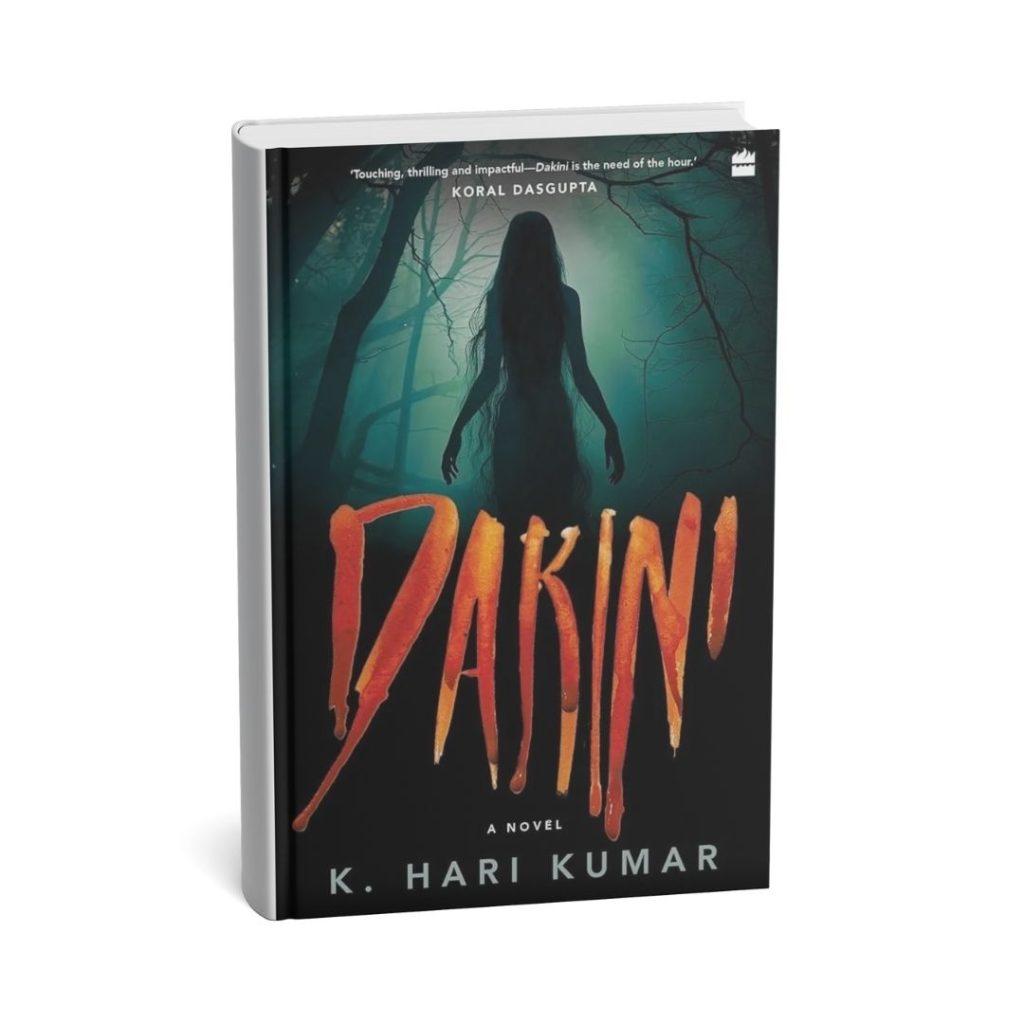

Take Mamta Mathews from Dakini. A modern, independent woman from Mumbai, she seemingly has all the freedom in the world. She is educated, she has the privilege to navigate the city as she pleases, and yet, she is bound by archaic patriarchal laws. Her personal tragedy—a terminated pregnancy that she never truly made peace with—leaves her hollow inside. But it is only when she finds herself in the middle of a remote village’s witch-hunt that she understands the depths of society’s cruelty toward women. Mamta, a journalist, believes in rationality, but she is thrown into a world where superstition is weaponized against women like Karmi Rani.

Karmi’s story is tragic beyond words. A woman from a remote village, she had no freedom to begin with. First, she was beaten by her husband. Then, she was blamed for his death. The villagers accused her of being a dakini, a supernatural witch, because they needed someone to blame. In the end, she was hanged from a tree while she was eight months pregnant. And her unborn child? Sacrificed.

Irony of the strong female characters in Indian fiction

Mamta, a woman from the city, and Karmi, a woman from the village, exist in entirely different worlds, yet they suffer under the same system. The only difference is in the degree of control. Mamta still has the illusion of agency—until she steps into a world where women’s rights mean nothing. Karmi, on the other hand, never had that illusion to begin with. The question that lingers is: is there truly any place where women can escape the grasp of a society built to control them?

For me, writing them was an exploration of how much has changed for women—and how much hasn’t.

Anahita & Mehr: Women Caught in the Past

Then there is Anahita from Dakhma. Her story is not about external oppression but about the scars that never fade. Anahita is a woman with a past that refuses to let go. She has survived something that most people don’t talk about—sexual violence (though this was left out from the final manuscript)—but she has never fully healed from it. She is stuck in a marriage where she is left vulnerable, where she hides her pain because society does not allow space for it.

Unlike Mamta or Karmi, Anahita’s fight is not against the outside world, but against herself. She exists in a limbo, never fully present, always slipping back into the nightmares of her past, while her present prepares to become another. And yet, even she must make a choice. Does she remain a prisoner of her trauma, or does she take control of her story? Not every woman’s struggle is about survival—sometimes, it’s about learning how to live again.

And then there is Mehr, another character from Dakhma, whose journey is intertwined with the weight of history and expectation. Mehr is caught between ideologies—she carries the burden of her ideology while being forced to compromise to the ideology imposed upon her by those who fund her organisation. Then there is her in complete love story, a hurt that has never healed until the woman she loved makes a comeback into her life again.

Unlike Anahita, who is trapped in her memories, Mehr is constantly reminded that her present is not truly hers to shape. Her struggle is a different kind of endurance, one where rebellion is quiet but no less significant. For Mehr, the question is not just about breaking free, but about whether she even has the right to do so. When society pre-defines a woman’s fate, can she truly rewrite it? But if she doesn’t rewrite then does she cease to be one of the strong female characters in Indian fiction?

Kalki’s Character in Bhram: A Different Kind of Strength

When Bhram happened, it was during the OTT boom, a time when streaming platforms were experimenting with stories that mainstream cinema wasn’t willing to take risks on. Kalki Koechlin’s character in Bhram is an interesting one because, unlike Mamta or Anahita, she isn’t actively fighting a battle. She is a passive observer, someone who is haunted—both literally and figuratively—by her past.

And yet, despite her vulnerability, she is the one who uncovers the truth. She doesn’t charge into battle, she doesn’t break free in an act of rebellion, but she survives long enough to see through the illusions around her. Her strength isn’t about force—it’s about endurance. And endurance, too, is a form of power. Not all warriors wield weapons; some simply refuse to stop searching for the truth.

The Challenge of Fiction with Strong Women

The thing about writing strong female characters is that they don’t always fit neatly into the boxes that people expect. In literary fiction, they are welcomed and rewarded. But when it comes to commercial fiction and film adaptations, the conversation changes.

There is always a macho hero or chocolate hero requirement—someone who is strong, who beats up bad guys, who “rescues” or ‘woos’ the woman. But what happens when the woman is the strongest character in the story? What happens when she isn’t waiting to be saved, when she is the one bringing justice, the one standing at the forefront of the battle?

It becomes a problem.

Filmmakers worry: Who will the male audience relate to? Who will be the “hero”?

And so, stories like Dakhma get pushed to the back. Executives ask for changes—”Can we make the male character more prominent?” “Can we add a love angle?” “Can she be softer, more likable?”—as if strength in a woman is something that needs to be toned down. The only time a female character ticks a box is when she is a homosexual (and not for the right reasons).

It is frustrating, but it is not surprising. Because the world still struggles with the idea of women who do not conform, who do not need validation, who take power into their own hands.

Why These Women Matter

Strong female characters in Indian fiction have always existed, but the question is whether the world is willing to embrace them as central figures. As I continue to write, I remain hopeful that stories like these will not remain exceptions but will become the norm—because these women, their struggles, and their triumphs deserve to be told, read, and remembered.

I don’t write these women because I want to prove a point. I write them because they are real. Because there are Mamtas in every city, Anahitas in every home, Mehrs in every broken generation, and Karmi Ranis in every forgotten village.

Their pain is real. Their rage is real. Their resilience is real.

On Women’s Day, I am reminded of why their stories matter—because we are still living in a world that tries to erase them.

But they will not be erased. Not in my stories. Not in life.

And now I sign off to write my woman character in my male-centric work.

Leave a Reply